A Holistic Approach for Technology and Quality Audits in the New Era of Computer Server Design and Manufacturing

Streamlining governing processes in audit execution and auditor training.

The supplier audit is one of the most powerful and effective supplier quality management tools. Supplier audits have played an essential role in supplier technology qualification and supplier quality assurance for years. However, it is necessary for the industry to review and renew its audit strategy at this critical time, so that supplier audits are able to address the new challenges in supplier quality management and continue to effectively mitigate quality risks.

A holistic approach to enhance the effectiveness of technology qualification and quality assurance audits is presented here. The approach is derived from IBM’s effort to address the challenges from both internal design complexity and external industry dynamics in the context of computer server design and manufacturing. This approach can also be used as a reference for the entire computing hardware industry, including consumer products. (This article does not include any IBM confidential information associated with its supplier audits.)

Approach: Governance Model and 3 Frameworks

Any modern computer hardware, either enterprise products such as computer servers or consumer products such as mobile phones and laptops, contains a range of technologies. A typical list of technologies includes semiconductors, IC packaging, passive components (e.g., capacitors), printed circuit boards, electronic assemblies, storage devices, power supplies, cooling technologies, cables, connectors, and mechanical components. In most cases, these technologies are now outsourced or procured through the supply chain and subjected to qualification and quality audits.

It is evident the above list of technologies covers a set of distinct engineering disciplines, which imposes a challenge for any attempt to propose a unified audit strategy within an organization. Therefore, a survey with roughly 30 technology and audit SMEs (subject matter experts) from IBM was conducted to better understand and characterize the challenge of generating a unified audit strategy. The SMEs who participated were experienced auditors who covered all the aforementioned technologies. The key findings and recommendations from the survey are:

- Different technology groups have different audit practices in specific areas due to the nature and diversity of the industries managed.

- Instead of issuing a list of specific guidelines, it is practical to set up a framework that governs the audit practices at a high level but allows flexibility for different technology groups to have their own practices.

- Suppliers appreciate customer audits performed by knowledgeable, technical auditors. Suppliers learn of new industry standards and best practices, and are benchmarked against industry competitors. They find value in thorough reviews of their manufacturing processes compared to the standard quality management system (QMS) review.

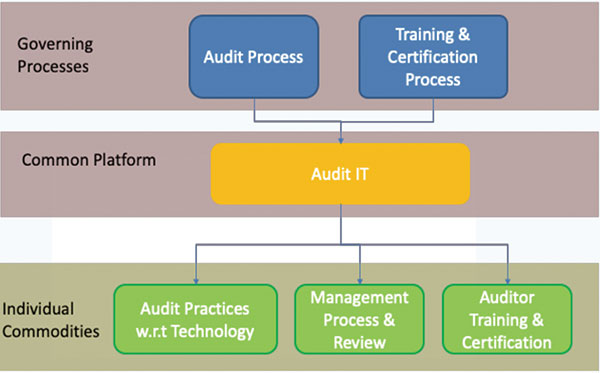

A governance model, illustrated in FIGURE 1, was proposed based on the key recommendations from the survey. It emphasizes the use of a common Audit IT platform to govern a common audit process and manage the training and certification process for general audit practices of all the auditors. The model also recognizes the distinct engineering technology disciplines must be empowered to define audit practices for their technology, establish management processes and reviews, and manage auditor technical training and certification.

Figure 1. Audit governance model.

It was highly recommended to set up a steering committee to manage the governing process and common platform. The steering committee has the following critical missions:

- Coordinate, execute and deploy the new audit strategy and framework across individual technology teams.

- Maintain and evolve the audit strategy and framework to meet organizational needs.

- Review and incorporate new initiatives into the audit strategy and framework.

- Coordinate cross-technology collaboration activities, IT development projects and training programs.

This article discusses key attributes of the governing processes and common platform (Figure 1). Details of the practices of individual technology teams are not in our scope. A case study from electronic card assembly and test (ECAT) is presented, however.

Audit Process

In the context of this article, Audit Process refers to the common audit workflow and associated definitions. These definitions include audit types, audit finding categories and audit rating criteria. On the other hand, Audit Practices refers to specific criteria or practice used by different technology teams to execute the common audit workflow. For example, IBM defines five finding categories in the audit process: positive, major, minor, improvement, and request for information. Each technology team has its own criteria to determine the actual rating based on the risk level of an observation with respect to technology, design complexity, and industry baseline and benchmarking. For example, weak statistical process control (SPC) practices could be rated a major concern in a wafer fabrication process but rated as an improvement item for a passive component manufacturing process.

In the holistic approach presented here, a governed audit process provides a common framework for audit execution, reduces undesired variation in audit execution, and ensures the feasibility of deploying the common IT platform. On the other hand, audit practices with respect to individual technology teams provide the flexibility to accommodate the vast differences between distinct engineering disciplines and avoid impractical audit execution that leads to inappropriate rating of the findings.

The actual boundaries between the governed audit process and audit practices with respect to individual technology teams may vary from organization to organization; however, these boundaries must be clearly defined and documented.

Auditor Training and Certification

The success of an audit largely depends on the skill and execution of the auditors. Therefore, auditor training and certification are equally important to the audit process.

The three components of skills and knowledge (TABLE 1) are equally important for an auditor:

- The quality management system (QMS) knowledge: the comprehensive understanding of various quality management processes (such as change control, nonconforming product control, documentation control) in a QMS (often with reference to ISO) and the ability to apply such understanding to determine the risk level of observations during the audit.

- Technology expertise: the comprehensive understanding of the manufacturing processes and functions of the products subjected to the audit, and the ability to apply such understanding to determine the risk level of an observation during the audit.

- Communication and interpersonal skills: soft skills essential for the smooth execution of an effective audit, including but not limited to professional behavior, ability to “listen” to different opinions, ability to handle difficult situations (for example, pushback by suppliers on certain findings), and ability to deliver clear technical communication.

Table 1. Auditor Skills and Knowledge

While the knowledge of a Quality Management System (QMS) and a specific technology can be taught in a classroom and assessed by a test paper, it requires a large amount of practice to transform the knowledge into skills. On-job-training (OJT) (i.e., shadowing with experienced senior auditors or audit experts in actual audits) provides the perfect platform for audit skill development. More important, communication and interpersonal skills can only be taught and assessed by OJT. Hence, it is highly recommended to have OJT as the core of the auditor training and certification process. The duration of OJT is recommended to be at least two years for new hires fresh from academia, but can be shortened based on the proficiency and industry experience of the auditor under training.

Similar to audit process, a governed Auditor Training and Certification Process provides a common framework for auditor education, reduces undesired variation in auditor training and prevents unauthorized auditor certification.

As mentioned, suppliers expect to learn the industry standards, best practice or benchmark in their industry or competitors through audits. On the other hand, each technology team has its unique audit practices. It thus makes perfect sense that each technology team is responsible to train its own auditors with respect to its audit practices, and is empowered to certify its own auditors.

From the auditor’s perspective, an auditor shall only be certified to conduct audits of the technology in which they are trained. If the auditor wishes to conduct audits of a different technology, they must be trained and certified by that other technology team.

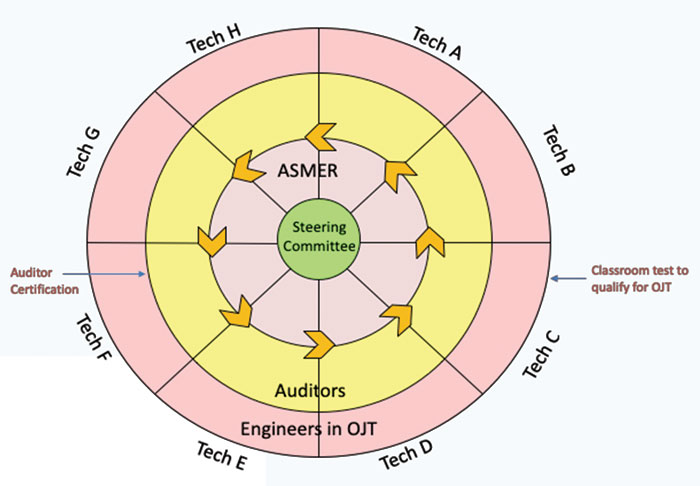

From the trainer’s perspective, it is highly recommended to define a group of SMEs within one technology who are responsible to teach and mentor new auditors in on-the-job training (OJT). One possible implementation of such a training and certification system is illustrated in FIGURE 2.

Figure 2. Implementation examples of audit training and certification system.

The steering committee maintains the governed Auditor Training and Certification Process at the center. Each slice represents a unique technology team. Each technology team follows the common framework for auditor education but has a group of Audit SME Resources (ASMER) that defines the training syllabus, provides OJT to new auditors and controls the certification for their technology team.

The system allows auditors to be trained and certified by multiple technology teams in the event there are business requirements for an auditor to manage multiple technologies. The system is also easily scalable for adding new technology teams.

Audit IT Application

Supplier auditing would greatly benefit from an IT solution that would deliver business process optimization, efficiency improvement and cost reduction. An IT application not only plays an important part to govern and deploy a common audit process and auditor training and certification process, it also enables use of data analytics and cognitive tools, which provide insights to auditors and management on audit planning, audit results review, and quality issue investigation/resolution.

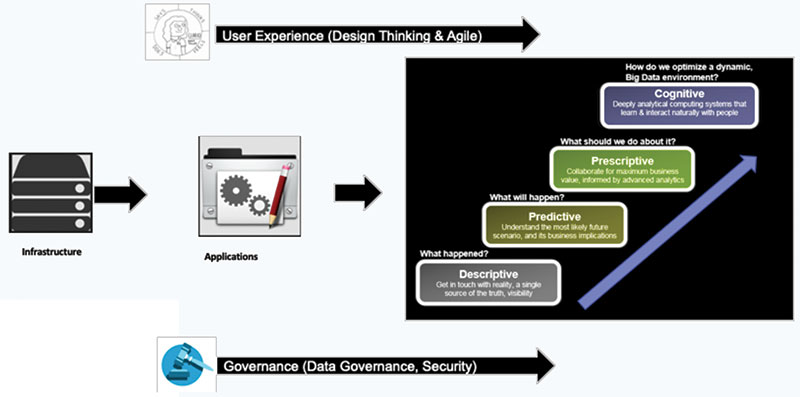

FIGURE 3 shows a recommended IT framework of enterprise solutions for the complex business processes required to perform supplier audits. This framework has been synthesized based on IBM’s experience in developing IT solutions for audits. The basic elements of the IT solution address scheduling, team assignments, an audit checklist to ensure all areas of the audit are addressed, documentation of audit findings, tracking of critical corrective action requests and ensuring all key elements are complete before closure of the audit.

Figure 3. Recommended IT framework for enterprise solutions.

For any application, a good user experience is the paramount objective. The use of Design Thinking1 is highly recommended for capturing user requirements and enhancing user experience. Incorporating Agile2 methodologies to this process ensures the constant delivery of enhancements to the user’s experience.

Infrastructure, data governance and security are critical foundational elements in the IT system architecture, impacting performance, analytics capability and compliance. The IT architecture design and optimization is outside our scope, but requires close collaboration between IT professionals and audit SMEs.

Enabling data analytics is another key area for audit IT solutions. Incorporating an appropriate data analytic solution will significantly improve the efficiency of audit planning and audit reviews. Among various levels of data analytics, descriptive and cognitive analytics (artificial intelligence) are key areas of interest for the audit process. Descriptive analytics can provide quick insights on audit planning, audit status, and top areas of concern. Cognitive analytic (artificial intelligence) solutions can assist auditors in audit preparation with a quick, complete and comprehensive summary of all historical data pertaining to an upcoming audit and provide key focus areas based on the history of the supplier’s product performance in other areas of the enterprise.

Case Study: ECAT Audits

To illustrate several of the concepts presented here, a case study is discussed. The example is provided based on actual experience and subject matter expertise gained from conducting electronic card assembly and test (ECAT) audits over the past decade, spanning worldwide geographies.

The example includes several fundamental concepts important to ensuring a robust audit framework. Each of the elements is discussed throughout this section:

- Communication to suppliers.

- Audit preparation and planning.

- Auditor training and skill.

- ECAT manufacturing facility audit execution.

- Closure of all nonconformances.

To begin, it’s important to determine what triggers an audit. Typically, there are five primary reasons why an audit would be necessary, including 1) a new supplier needs to be assessed for capability, 2) a new location with an existing supplier needs to be evaluated, 3) time since the last existing supplier audit has exceeded evaluation frequency requirements, 4) recent quality, reliability or operational issues have been identified with a supplier, or 5) new technology, capability or infrastructure needs to be evaluated at a supplier.

Communication to suppliers. Regardless of what triggers an audit, a critical first step is to inform the supplier a facility audit is requested. At this point it is important to communicate how long is needed to conduct the audit, confirm available dates with the supplier, and conduct pre-meetings to communicate key items and focus areas. The audit team responsible for the assessment should be identified and communicated at this time. During these early discussions, it is important to understand what products are currently built. A review of all auditable sectors and the proposed agenda should be included, along with any desired sharing of technology/product roadmaps. Finally, the supplier should begin to complete any audit checklists, forms, capability matrices, or other documentation provided by the audit team.

Audit preparation and planning. In parallel with supplier communications, the audit team should conduct planning efforts. The goal here is to develop key focus areas of interest that define key auditable sectors and the audit schedule/agenda. Some example areas of assessment can include early engagement capability, new product introduction processes, safety, IT security, failure analysis, traceability, process change management and test strategy/tester utilization.

To gain a better understanding of focus areas of interest, the audit team should review previous supplier audit records to understand previously identified key findings and improvement areas. Once defined, the schedule, agenda, and auditable sectors listing should be loaded into a central database repository (audit record) and communicated to the supplier.

Auditor training and skill. The effectiveness of an audit depends very much on the skill of the auditors. It is, therefore, extremely important to ensure the auditor’s skill and experience levels are high across multiple disciplines, including (but not limited to) manufacturing operations and infrastructure, quality controls, logistics, product assembly flows, safety, materials/inventory management, test protocols, and specifications/documentation controls.

To ensure this high level of skill, it is recommended auditor training includes both in-class learning sessions, and onsite audit experience with experienced audit coaches. In-class training sessions should be held to highlight, remind, and teach requirements for all auditable sectors. In-class sessions should be taught by senior auditors who can communicate the end-to-end process, as well as “tricks of the trade” learned from years of audit experience. Onsite audits can be conducted by senior (lead) auditors, or for training purposes, by auditors-in-training. In this latter case, auditors-in-training can lead the audit team with senior audit coaches helping as necessary. This on-the-job training is critical to building confidence and experience levels for new auditors.

Conduct ECAT manufacturing facility audit. The next step in the process is for the ECAT OEM audit team to travel to the supplier facility and conduct the audit. Auditors-in-training are encouraged to lead the audit (when possible), with senior auditors acting as coaches and supporting members of the audit team. Two groups make up the audit team: members from the OEM audit team that requested the audit and members from the supplier working directly with the OEM team. To be effective, keep the audit team small. The audit agenda should be closely followed with time spent in meeting rooms to discuss base process flows, but the majority of time should be spent on shop floors, throughout the facility.

During the audit, conduct infrastructure/systems-level testing, product inspections and manufacturing operations reviews. Communicate identified issues to the team immediately, and record and summarize identified issues at the end of each day of the audit. Once all auditable sectors have been reviewed within the facility, hold a closing meeting to communicate all identified issues, along with the severity level of each finding. Issue a final report to the supplier highlighting the overall assessment of the audit (either acceptable or unacceptable), along with a list of required corrective actions to be addressed and closed by the supplier.

Drive closure of all nonconformances. After the audit team conducts the audit and returns from the supplier facility, schedule corrective action request (CAR) meetings. This process step converts audit findings into follow-up action items for the supplier to provide continued improvement and closure. Leading the CARs meetings is another opportunity for an auditor-in-training by working directly with the supplier on new correction action solutions. It is recommended that a weekly or biweekly meeting be set up to ensure timely closure of all identified items. Closure of the items can typically range from one to six months, with some cases lasting as long as nine months. Once all corrective actions have been resolved with new solutions – in place, and verified – the audit record can be updated and closed.

Benefits to the Approach

There are several benefits of using the audit framework described in this case study, including:

- Uses a standardized method, tools and documentation (checklists, agendas, reports) to conduct an audit.

- Focuses on clear communication between audit team members and the supplier under evaluation.

- Ensures strong cross-functional skill levels of auditors.

- Enables training of new auditors; learning/coaching directly from senior auditors, which consists of formal in-class training and OTJ training with actual audit experience.

- Drives closure of all identified corrective actions with suppliers over a period of time following the audit.

- Focuses on continuous improvement over time; working to reduce/eliminate significant issues with suppliers.

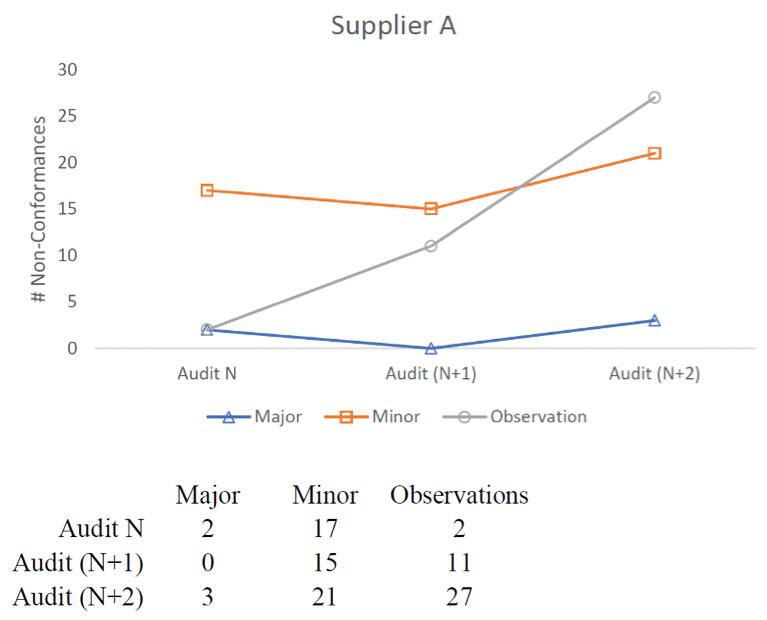

To summarize this case study, two supplier examples are illustrated below. Supplier A and B are both existing suppliers with experience working to the OEM’s quality, operational and reliability requirements. In both cases, supplier performance is monitored over a period of three consecutive audits.

In FIGURE 4, Supplier A continues to struggle to achieve desired performance levels. Repeated major nonconformances can be observed, along with increasing levels of minor nonconformances and observations. This result is unacceptable. This case shows the number of identified issues is not reducing over time, despite the best efforts of the audit team. Continued focus and engagement with Supplier A is needed moving forward.

Figure 4. Supplier A (struggling to improve).

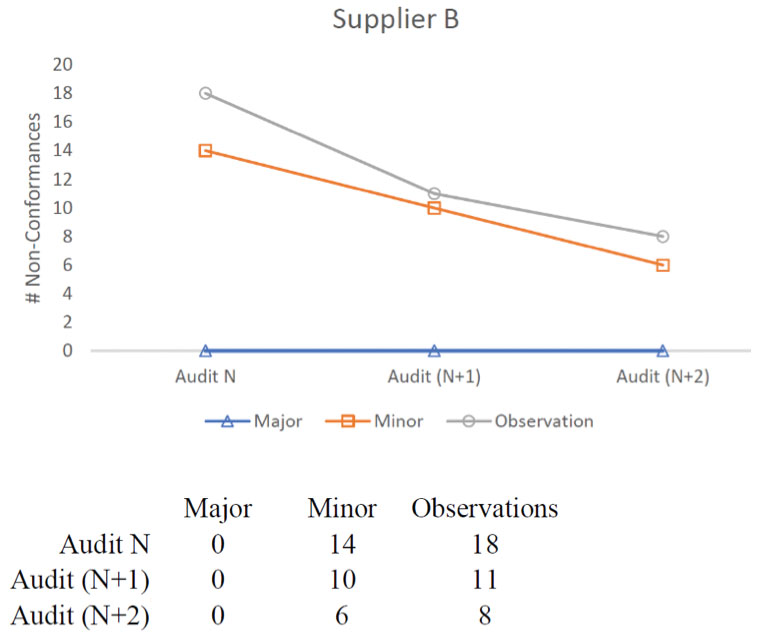

FIGURE 5 shows the performance of Supplier B. In this case, during the last three audits, no major nonconformances were found, and a decreasing trend in minor nonconformances/observations was observed. This example shows a desired response when working with the supplier over a period of time, as the total number of nonconformances continues to be minimized. This is the goal of the audit approach and is considered an acceptable result.

Figure 5. Supplier B (Continuous improvements made).

Conclusion and Recommendation

The authors presented a holistic approach to enhance the effectiveness of supplier audits. The approach emphasizes the balance between governance and flexibility. It provides a verified solution to address the challenges of managing distinctive engineering disciplines and technologies in the supply chain. As the market and industry will continue to be dynamic, it is important to reanalyze the market and industry situation (including design complexity trending) from time to time and capture new challenges. The supplier audit strategy and its approach then need to be reviewed and transformed to address those new challenges.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Wei Guo, Jeff Komatsu, Wen Ming Lim, Wayne Weifeng Zhang, Queena Lin Zhao, Grady Zhipeng Wang, Isaias Rafael Jr Burao Angeles, Susan Junjie Zhai, Benjamin Puay Jiang Toh, Dave Verburg, Brian Beaman, Todd Brightly, Pui-Shan Hou, Eric Swenson, Wen Wei Low, Merry Rui Ma, Jason Lingle Guo, Tan V Nguyen, Scott Lockaby, Callum Foshee, Marie Cole, Rick Fishbune and Lynda Anderson for their contribution to implement this approach in the IBM system supply chain.

References

1. IBM website, Enterprise Design Thinking, ibm.com/design/thinking.

2. IBM Agile DevOps, ibm.com/ibm/devops/us/en/agile.

, , , , , , , and are with IBM; (ibm.com) xuef@sg.ibm.com.