3 Days with EMS in the Valley

Profiles of three Bay Area contract assemblers show varied strategies for success.

The Silicon Valley is unmatched worldwide in its depth and breadth of technology development, to say nothing of the speed those technologies are conceived and realized. And perhaps nowhere else in the world has the same density of EMS companies to build those products. CIRCUITS ASSEMBLY tracks more than 250 companies in the area, and there likely are many more.

For every plant, large or small, there are almost as many business models. On recent trips to the area, our editors visited and spoke with three companies that are blazing very different trails on their paths to success.

SunnyTech/Kaga: Growth by Partnership

First up was SunnyTech. At first blush, the San Jose company seems like a typical NPI shop. Formed in 2001 under the guidance of Virgil Chen, SunnyTech has grown to 40 staff in the US. The 5,000 sq. ft. plant features one SMT line, with an Icon screen printer, two Yamaha YS12 placement machines, a Heller reflow oven, and Ace selective solder. Offline AOI is used on-demand only. Volumes are on the low side at SunnyTech; 5000 pieces would be a big order. It handles about 50 to 100 new programs a month, and about 80% of the local business is consigned. Along the way, it has added box-build operations and a warehouse, bringing its combined size to about 60,000 sq. ft.

It is with the box-build that a new opportunity emerged. One customer was Kaga. While many might be unfamiliar with the Japanese conglomerate, Kaga has a long history in the Silicon Valley. Also, it is huge.

Kaga was founded in 1968 as an OEM supplying transceivers and monitors. Starting in 1981, its Taxan brand monitor (the KG-12) could be found in the Apple II. That relationship with Apple expanded into distribution, which became a second of the three-headed business operation. In 1992, the company launched its EMS segment. From its start in Hong Kong, plants have been added in the US, Czech Republic, Thailand, Malaysia, Mexico, and two in Shenzhen. Japan is the center for logistics and sales offices. The company now boasts more than 5,400 employees and more than 85 SMT lines across nearly 850,000 sq. ft. of factory space. The EMS business has now reached about $750 million in revenues a year. Automotive, industrial and medical are key end-markets, and every shop is now ISO 13485, except Mexico.

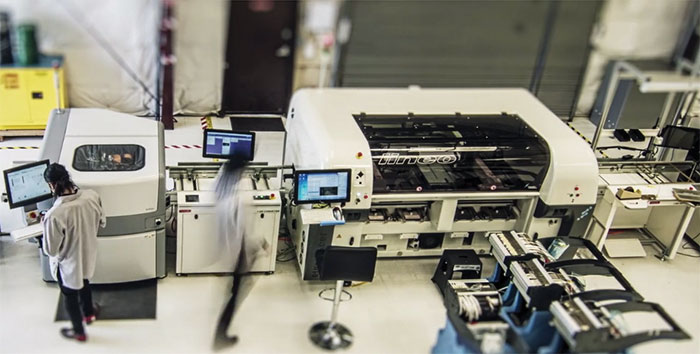

Figure 1. Kaga SMT line in Shenzhen, where it has two plants.

Kaga puts great emphasis on concurrent engineering. Equipment sets are similar across all the sites. General managers for the EMS sites typically come from the sales side. Kaga follows traditional loading practices. Engineers in Japan perform the research for next-generation programs.

Kaga’s model is very customer-centric. Three sites in China are tied to a specific customer (a large HVAC company). Similarly, its plant in the Czech Republic is dedicated to that same company. And the sites in Thailand and Mexico, which came online in late August, also supply to that company. EMS is very much a part of its growth strategy. Managing directors of each site report to a VP in Japan, who reports to the CEO. And at least one board member sees EMS as potentially the biggest growth area for Kaga.

SunnyTech formalized its partnership with Kaga in 2014. (Kaga also has two partnerships in China.) From Kaga’s perspective, it gives the firm a foothold in the key geographical region as it tries to open up to more non-Japanese customers. It has three key customers in the US, for which it performs considerable NPI work, prototypes, and backend support such as repair and rework.

Industry veteran Terry Kearney was brought on in 2016 to help grow the Kaga business in North America. According to Kearney, the company occasionally leverages its component and distribution businesses to find new customers. “This helps get through to the key engineering guys,” he says. “The suppliers are the first people who get called during the design phase.”

Figure 2. Kaga workers perform testing.

Noting Kaga’s emphasis on low-volume builds, he says Kaga is in a good position to handle most OEM work, but patience comes in handy. “We are probably better suited than Tier 1 companies to do smaller volume programs, but have to wait on occasion for the OEM to ‘fail’ with Tier 1s.”

Both firms have expansion plans. Kaga is courting a potential customer in Pittsburgh and could open a plant there. It also has partnerships with sheet metal, cable and other manufacturers that could eventually lead to future EMS work, too.

SunnyTech is considering a move to a 15,000 sq. ft. factory in the first half of next year, where it would combine its EMS and box-build operations. Plans call for adding another SMT line at that time.

Rocket EMS: Spearheading Industry 4.0

Rocket EMS can be found in one of the many unassuming buildings in Silicon Valley, but don’t let the modest setting fool you. Inside Rocket EMS, a data software revolution is taking place, and Rocket EMS isn’t even a software company.

Three years ago, the Santa Clara-based manufacturer commissioned its own MES/ERP software: Voyager, now in version 6.0.

“This is what Industry 4.0 can be,” said Craig Arcuri, once the firm’s CEO and now a consultant. “There is nothing on the market that does what you’ll see here at Rocket,” he said during a recent small-group tour of the Santa Clara headquarters.

He defined Industry 4.0 as “complete interconnectivity,” and after a checking out the facility and watching a software demo led by the firm’s president, Michael Kottke, it’s clear this is one manufacturing firm that has that concept nailed.

“Rocket is working on Industry 5.0. Let’s write AI software,” Arcuri said. “At the end of the day,” companies want to “capture data.”

Rocket has a staff of software engineers, three onsite working on Voyager every day. Among the myriad EMS companies in the Silicon Valley, this is one of the ways Rocket stands out.

During the tour, Arcuri pointed out a program management and materials support staff. Rocket has 10 program managers handling more than 200 customers with “spectacular customer service,” which, he adds, is not possible without a data system. The key, Arcuri said, is to “always say yes to the customer.” Yes is the first step. Determining the process is second.

When he opened the doors to Rocket’s factory floor, we were reminded, oh yeah, the company builds boards too – impressive ones, we might add. The manufacturing floor was a long, rectangular shape. Products start on one side of the room and finish on the other – a practical, efficient use of space.

“Product changeover” happens in “35 seconds,” Arcuri said. “That’s Nascar changeover.”

CIRCUITS ASSEMBLY observed multiple Juki placement machines, as well as ViTrox and Nordson Dage inspection systems. Rocket performs 100% SPI on every board. It also performs flying probe and ICT, and a significant portion of the space is used for system integration. Employees at each station scan in and scan out, as do products. Rocket boasts a PCB layout group on the floor as well.

“Ask the company a question, and [Rocket] can show you data on a screen just like that,” said Arcuri, a claim Kottke proved firsthand during a post-tour software demo.

Kottke wasn’t shy about sharing Voyager’s attributes on a large screen in one of the firm’s welcoming meeting rooms, citing passion as the reason for its astounding capabilities. This guidance control system “controls everything. Everything we do is data collection,” he said.

Here are just a few examples of data that can be found inside Voyager at Rocket EMS:

- Employee training records (The software alerts staff members if they need to be retrained on any documentation.)

- Real-time hours, including breaks and idle time

- Labor tracking reports

- Work orders, including labor minutes

- Tracking of serial numbers of solder paste cartridges

- Reflow profiles

- A module for scheduling

- A records portal log

- Labor breakdowns

- Costs to the minute

- Profitability reports

- SMT efficiency tracking.

The list goes on.

Earlier Arcuri said Rocket “knows where drivers are at all times,” and customers have access to solder data, x-ray images, and many other types of data concerning their products.

The firm also has its own IPC training certification, Kottke said. “We evaluate our tests over and over before we certify our people.”

In the process steps, they “try to control errors.” Alerts are sent out in 15-minute increments when there are issues, and it’s rare for an issue to go unanswered after 30 minutes.

Through Voyager, they check out the top 10 defects daily to tie those to processes, procedures or people. “We can tell which solder works best on which board,” Kottke added, and Voyager is ideal for rescheduling.

He said he doesn’t mind sharing with the industry what this software can do because “the whole world has to get better.”

Rocket EMS is looking toward incorporating predictive technology and is working with Juki and ViTrox to pull data directly into Voyager.

From what CIRCUITS ASSEMBLY witnessed, possible applications for Voyager are limitless, and Rocket EMS has a fine future leading the Industry 4.0 charge – and, of course, it will continue to make top-of-the-line PCBs too.

Tempo Automation: Hardware from Software

Fifty miles north, in San Francisco, Tempo Automation also started with a revolution in mind. Four years ago, the founders tried to leverage 3D printing technology to develop an assembly machine that would do PCB assembly – solder paste, placement and inspection in one machine.

Along the way, founder Jeff McAlvay realized there’s a bigger market for a hands-off experience, one in which Tempo could build the entire assembly itself, while also solving some of the pain points, such as DfM problems, parts availability and pricing. “The idea,” explains Jesse Koenig, now vice president of technology, “is we can integrate all that upstream into the design and ordering process and take care of that with software, so when a customer thinks they are done, they are done.”

None of Tempo’s founders hail from contract electronics manufacturing. CEO McAlvay came from McMaster-Carr, a large industrial supply company he likens to a DigiKey for mechanical parts. There, he would tinker with software. And he listened to electrical engineers who wanted more from their assemblers.

“None of my friends seemed to have an outfit they were in love with. Then we visited a number of these outfits and saw their quoting, component ordering, machine setup – so much of it was manual, and we felt a software-centric approach could be impactful.” Noting the simplicity of the Compile button, he wondered why there wasn’t one for ordering and producing electronics.

Koenig was in guidance and control engineering, where he developed expertise in Matlab and Simlink to develop algorithms for spacecraft. He met McAlvay at an industry meetup, and was driven by his vision. “I was coming from aerospace, which has very long projects encompassing many years. Things would get cancelled. I wanted something more immediate.”

Figure 3. Tempo Automation is overlaying sophisticated software quoting and DfM on its assembly operations.

McAlvay was working on a robot, while Koenig was intrigued with solving a consumer electronics problem. The two decided to merge their ideas. “Jeff said, ‘If we can solve that, it solves a lot of technology problems,’” Koenig recalls. “There’s a ton of contract manufacturers, but we didn’t think they were doing it the way it should be done. So if we do it the right way, we hope we can grow the market by allowing people to prototype boards more easily. The turn time is so much faster. Our quality is getting better all the time as we do more automated inspection. We think through our use of software we can differentiate.”

The eureka moment came when Tempo’s founders decided not to pursue its own robots. “There was a lot of R&D still to go to make those robots work reliably and for all the uses they would encounter,” says Koenig. “The robot wouldn’t have solved issues with reflow, through-hole soldering and inspection. So now we buy the best off-the-shelf equipment we can and focus on factory automation software. The goal is to modernize contract manufacturing and become the gold standard for people who need fast, seamless manufacture.”

Tempo often makes upgrades to the software several times a week. “We feel we should be rapidly iterating, much like we ask our customers to do,” explains McAlvay. “(When doing upgrades) we do feasibility studies so the software stays intuitive.”

As its name suggests, Tempo Automation is about speed and ease of use. It offers three-day turns in the Bay Area and four days elsewhere in the US. Its software works like this: Customers upload bills of materials and CAD. The tool indicates if a part is not available, and issues alerts if a part number is omitted or mis-entered, or if the number of parts doesn’t equal what’s on the file. It also verifies the reference designators match the quantity.

The user then specifies the board parameters and quotes the quantity. (Currently the limit is 100 boards for a three-day turn.) The software then reviews the board for blind/buried vias, stackup, minimum lines and spaces, and calculates turn time. Finally, it issues a quote indicating delivery time, component cost and price per unit.

Tempo is optimized for Altium but accepts other CAD types and Gerbers, although the latter slows the quote process because it requires human intervention.

There are plans to add DfM into the software, initially to point out problems, orientation of diodes, and ways to cut down time, and eventually to look for BoM-to-CAD mismatches.

Tempo consists of 45 staff, including five software engineers and a pair of process engineers. Most customers are smaller, newer companies, but Koenig allows Tempo has “five to 10 customers” that are easily recognizable. Typical customers include R&D groups at large companies; product development consultancies; funded hardware startups and small- and medium-sized businesses.

Capital investors are providing funding, and the plans include moving to a larger manufacturing facility next year. They want to stay in or close to their home city.

Explains Koenig: “San Francisco continues to be a hotbed of tech innovation – software and hardware. A lot of people here have meetups, conferences. We like to be close to that energy and close to investors, and San Francisco is a great location to attract the best software engineers in the world.”

Not surprisingly for an electronics company that acts like a software company, the key metrics are different from traditional EMS and include the number jobs that can be auto-quoted without any labor input, and the percentage of repeat customers. Another is the number of orders vendors ship to Tempo in one day, which permits it to maintain its breakneck delivery pace.

As part of its growth strategy, McAlvay says investment continues in a “software-centric approach” to the manufacturing process. “The implementation of the vision has changed, but the notion of what we aspired to do has been consistent. And I think we’ve made material progress on that front – how many times a customer uses the given software for their order.

“Software really is a marvelous tool to draw on the breadth and depth of experience that would be difficult any other way. We’re very bullish of software having a transformative effect on the manufacturing side.”

is editor in chief and is senior editor of PCD&F/Circuits Assembly; mbuetow@upmediagroup.com.

Press Releases

- Johan Stormlund Joins Inspectis AB as Marketing and Sales Manager, Industrial Applications

- Altus Brings Heller’s Revolutionary Short-Cycle Vacuum Reflow Oven to the UK and Ireland

- High Density Packaging User Group Announces European Space Agency Membership

- High-Density Packaging User Group Announces ASKPCB Membership